10(19)#20 2021 |

|

DOI 10.46640/imr.10.19.8 |

Jelena Hadžić and Marina Baralić

Presscut d.o.o., Fakultet hrvatskih studija Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, Hrvatska

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Presscut d.o.o., Zagreb, Hrvatska

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Humor in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Puni tekst: pdf (3870 KB), Hrvatski, Str. 3069 - 3110

Abstract

The research is focused on the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Croatia – March 2020. The subject of the research are humorous messages related to the pandemic. By combining quantitative and qualitative methods, this research showed how the interviewed respondents experienced the received humorous content related to the coronavirus and what content characteristics of the humorous messages were detected through the content analysis.

Key words: Covid-19, coronavirus, reception of humor, content characteristics of humorous messages.

INTRODUCTION

We are truly lucky to be living in a society (and time) that is capable of laughing in the face of adversities. A historical review of the theory of humor, up to the 18th century, describes humor and laughter as a mostly negative and socially unacceptable phenomenon (Morreall and Raskin).

We are also lucky that our reality is such that the emergence of just one highly contagious, deadly disease that has no cure or vaccine is something extraordinary.[162]

On 5 January, the World Health Organization announced on its website that several cases of pneumonia of unknown cause had occurred in Wuhan[163]. At the time of writing this paper, the number of detected cases has surpassed 28 million cases worldwide[164]. During the observed period (March 2020) this number ranged between 91,086 and 941,042 recorded cases worldwide[165] and between 7 and 867 patients in Croatia in the same period[166].

March 2020 proved to be an extraordinary month in recent history. Countries entered lockdown[167] one by one. The first European country to declare lockdown was Italy, on 9 March 2020, which sent a strong message to Croatia that the same scenario was at its door, and this became a reality two weeks later, on 19 March 2020.[168]

Torres et al. (2020) concluded “Indeed, humor has the ability to capture and narrate what has transpired peoples’ lives during a particular period, such as the COVID-19 pandemic,” and this is exactly what the authors tried to show in this research in Croatian circumstances.

Given that this paper deals with humor, it is necessary to first define “humor”. Philosophers, psychologists, lexicologists, scientists and other thinkers have been studying humor since the time of Plato, but have not yet reached a consensus on its definition. One of the problems in defining humor is certainly the fact that the term “humor” changes meaning over the centuries (Morreall and Raskin, 2008, p. 211). Looking only at the last century or two, the notion of humor has taken on the forms and meanings as we know and describe today. However, there are too many definitions to list them all here, so for the purposes of this research, we decided to pick one, the general definition from the online Encyclopaedia. Humor is the “…common name for written, graphic and verbally presented content that evokes laughter and joy, but also for a personality trait that is manifested in humor and wittiness.”[169] Also, we should take into account that there is a difference between humorous and funny, as stated by Tkalac (2008, p.11); neither is the consequence of humor always laughter, nor is the cause of laughter always humor.

There is a lot of research on the positive effects of humor, so Yovetich, Dale, and Hudak (1990) showed in their research that humor has a beneficial effect on reducing stress in anticipation of pain. Bizi, Keinan, and Beit-Hallahmi (1987) have shown a connection between an assessment of a soldier’s humor by comrades-in-arms and an assessment by superiors about who responds better in situations of increased stress. Berk (2010) also cites psychological and physiological benefits: “Humor produces psychological and physiological effects on our body that are similar to the health benefits of aerobic exercise.” Kertcher and Turin (2020) suggest “Humor provided a tool for coping with stress and comfort in the shadow of isolation, unemployment, and the horrors of death.”

Torres et al. (2020) note: “Humor is shaped by culture, is subjective and requires cognition.” And that “Indeed, humor has the ability to capture and narrate what has transpired peoples’ lives during a particular period, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.” The references on humor in the age of dramatic/key/catastrophic events speak of two approaches, one of which says that humor is a way of coping with unpleasant events, advocated by Morrow (1987) and Dundees (1987), while Oring (1987, p. 276) offers a theory that the emergence of disaster humor is associated with media coverage of a catastrophic event in the mass media, and that jokes are only a form of rebellion against the “discourse of disaster.” Gubanov, Gubanov and Rokotyanskaya (2018) conclude: “Thus, ‘disaster humor’ can be seen as a revolt against tragedy escalation, as well as against the way journalists cover events, looking for the slightest ‘delicious’ details.” On the other hand, Kuipers (2002) wrote about how humor appears even in the first days of catastrophic events, which corresponds to both the first and second approaches to humor in dramatic events. Kuipers (2002) also states that “In the new Internet jokes, this connection with media culture is even stronger than in oral jokes. Not only do they refer to media culture, but Internet jokes are visual collages assembled from phrases and pictures taken from popular media.” Semmel (2020, p.94) concludes, “In the face of pivotal events, coping humor responds to audience’s needs in real-time by creating a distraction, a bonding opportunity, and a space in which people who want to hold onto the elicited emotions for a little can do so in a less harmful way.” While Tkalac (2008, p. 98) noted, “It is believed that the event thus becomes less real, and as such less frightening.” Henman (2001) supports this theory when he talks about prisoners of war in Vietnam in the 1970s and states that “These men relied on humor not in spite of the crisis but because of it.” In the same paper, Henman (2001), talking about how prisoners lost control of the situation, states, “But they did have control over one thing, and that was their humor perspective.”

Several humor-related studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic: Kercher and Turin (2020) who studied memes in Israel; Oduor and Kodak (2020) who studied humor as a means of dealing with the crisis event in Kenya and Torres et al. (2020) who made a discursive analysis of humor in the Philippines.

What this indicative research aims to achieve is to investigate what was on the minds of Croatian citizens at the time of the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, in March 2020. Through the prism of humorous content, shared by interpersonal and group online communication, we will analyse all the ways in which everyday life has changed, how citizens’ perception of certain phenomena/characteristics has changed, what mood prevailed and what emotions prevailed. As Chimuanya and Ajiboye (2016) wrote, even beyond the humorous benefit itself, the messages that humor carries can speak about social problems and help solve them.

All of the above formed the problem of the research – how humorous content related to COVID-19 was experienced at the very beginning of the pandemic in Croatia and what the substantive characteristics of that humorous content are.

RESEARCH GOALS

The goal of the research is to find out what was being communicated through humor in March 2020 and how this was received. This goal can be divided into two complementary main research goals:

1) What is communicated through humor?

- Find rules and categories of humorous content

- Explore types of humorous content

- Extract themes of humor

- Identify the audience of the humor – groups and/or individuals

- Record the presence of irony, sarcasm and dark humor.

- Record the presence of an educational note of humorous messages

2) How did the recipients of the humorous content experience the humor related to COVID-19?

- Detect whether humor had a positive or negative impact on them

- How do respondents assess the effect of humor?

- To connect respondents’ affinity to use humor in stressful situations with their impression of the impact humor has had on them

METHODOLOGY

Two research methods were used in the paper: content analysis and interview.

a) Content analysis

The studied corpus consists of humorous messages sent through digital channels in interpersonal and/or group communication. Why interpersonal and group communication, and not mass media communication or public communication on social networks (one that has no known recipients)? Mass media communication and communication that has no known recipients have a kind of self-censorship of content because the sender does not know (personally) all the recipients and is wary of the possible offensiveness of the message. The communication between recipients and senders who know each other personally is not so much burdened with socially responsible and politically correct expression, rather, a certain amount of understanding and tolerance is expected and implied, whereas personal acquaintance provides a framework for auto-selection of offensive and unacceptable content based on the knowledge of preferences, attitudes, opinions and other characteristics of the recipient. In addition, personal acquaintance provides broader limits of tolerance towards marginally acceptable content because the recipient is expected to cushion the controversial content elements based on the acquaintance. For these reasons, the materials used in the research are richer than the materials that would be available through the use of public communication. The researchers first tried to analyse the collected corpus of public communication, i.e. open profiles on social networks. The content that is at the same time humorous and refers to COVID-19 proved to be rather scant, which is another reason to direct research towards interpersonal and group communication.

The researchers focused the research on communication through communication services and social networks, in which the sender of the message knows the recipient or group of recipients and not one in which recipients were unknown.

Researchers recognize the problem of representativeness of the sample of analysed humorous messages, and the conclusions obtained by this research have no weight or the possibility of generalisation to the population.

It is true that communication platforms that serve as channels for transmitting interpersonal and group communication have all the messages, images, audio and video content sent by users stored in some place, but this data was not available to researchers. It is also necessary to note all legal restrictions, primarily related to privacy rules, which also represent a significant problem in obtaining population data for a study.

The observed period refers to March 2020.

The unit of analysis is a single post (or message) that can be in the form of text, image, a combination of text and image, GIF or video. The analysis includes textual, audio and visual elements of messages. The unit of analysis also includes accompanying content, mostly text, added to the post submitted by the sender, because a review of humorous posts showed that sometimes humor is manifested in a combination of accompanying and shared content.

- The categories of analysis are

- Type of post

- Time of receiving and sending a message

- Tags or keywords

- Reach of humor (international or local)

- Appearance of public persons, institutions or groups (entities)

- Target of humor

- Existence of sarcasm, irony or dark humor

- Humor messages

- Emotions contained in a humorous message

- Prior knowledge required to understand humor

- Humor topics

b) Interview

In order to supplement findings and gain better insight, the researchers conducted a semi-structured interview. Because conversation works like magic.

The main goal of conducting a semi-structured interview was to find out how the respondents experienced humorous content related to COVID-19 following the onset of the pandemic in Croatia, during March 2020. Almost all respondents were from Zagreb and the surrounding area. A total of 22 interviews were conducted, in January 2021.

Given the epidemiological restrictions that have been in place since the onset of the pandemic, the interviews were conducted via video conference.

As control questions, respondents were asked to describe what they remember from March 2020 and how they experienced those events.

The specific objectives were to:

- Investigate whether respondents noticed changes in the number and content of humorous posts they received and/or sent in March 2020,

- Investigate the ways in which humorous content has influenced them,

- Investigate to what they attribute the impact the humorous content had on them.

In addition to the interview, each respondent completed a short “coping humor scale” survey to examine the relationship between questionnaire results and responses and the explanations given by respondents about the manner and impact of humor on them personally. Coping humor scale is taken from “Humor, the psychology of living buoyantly” by Hubert M. Lefcourt, 2001, page 173. Coping humor scale is a questionnaire composed of 7 questions with answers on 4 levels of the Likert scale, which serves to assess how much an individual is prone to use humor when dealing with stressful situations.

At first, the views and opinions of the researchers seemed universal and true for all. However, as has already been said, “People see what they want to see” (O’Toole, 2013, p.3), so this research also revealed differences in opinions and attitudes through the interview.

The semi-structured interview has thirteen items, as follows:

- Remember March 2020. Please describe, in your own words, what happened then.

- How did you feel?

- Would you say that these feelings are weaker, stronger, or of the same level as before (say in February or January 2020)?

- Were positive or negative feelings prevailing?

- What would you attribute those feelings to?

- Do you remember receiving and/or sending humorous content in March 2020?

- Did those humorous messages have any effect on you? Describe and explain.

- Have you noticed (in March 2020) a change in the total volume of humorous content received compared to the previous period (e.g. in January or February 2020)?

- Did you notice a change in the content of the humorous posts (what was it about/what were you laughing about)?

- Have you noticed the educational function of humorous content, that is, have these humorous messages influenced people to behave in accordance with the recommendations?

- Do you still find these humorous posts funny?

- List the top five posts from that period.

RESULTS OR WHAT CAN BE LEARNED FROM HUMOR?

Every communication, even a false one, contains at least a grain of truth. It may be an exaggeration to claim that humor is a lie, but humor can be (and often is) a distortion of reality. Therefore, starting from the fact that every communication is a message, the aim of this research is to notice which changes in everyday life were the subjects of humorous messages and how the topics of humor are treated.

What underlined almost all analysed messages is the fear of a new invisible threat.

a) Content analysis

Change in perception

The newly-promoted rules of conduct have led to a shift in perception in such a way that new circumstances have made something that is otherwise unacceptable or inappropriate, acceptable and commendable; the essential has become irrelevant in the light of a new, “invisible” threat. In light of this new fear, humor is a response that puts into perspective the diminished value of what is otherwise frightening.

So, for example, bank robbers have become less scary than possibly contagious people wearing masks in public, the political question of where someone was during the war is no longer as important as the question of whether you are contagious and have spent 14 days on a skiing trip, and a person drinking alone in their house used to be considered a lonely person and a drunkard, and now they are becoming an example to others who are perhaps still going out and getting together for a drink.

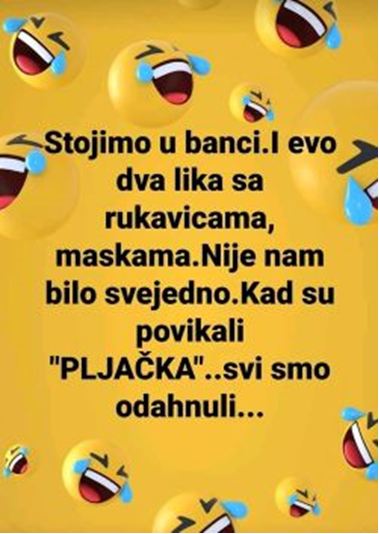

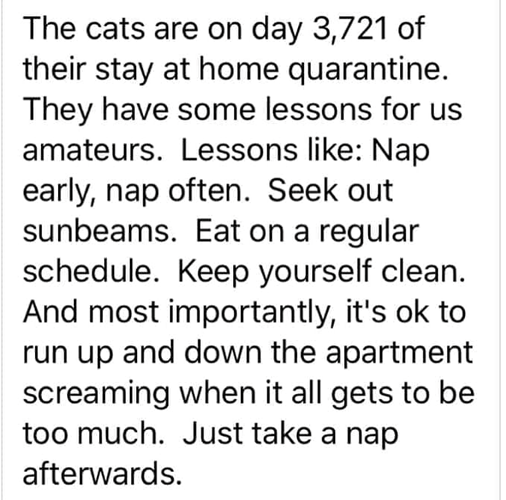

Example 1 Change in perception A

(we were in bank. Two masked guys with gloves appear. Situation got tense. When they yelled “ROBBERY”.. we were all relieved…)

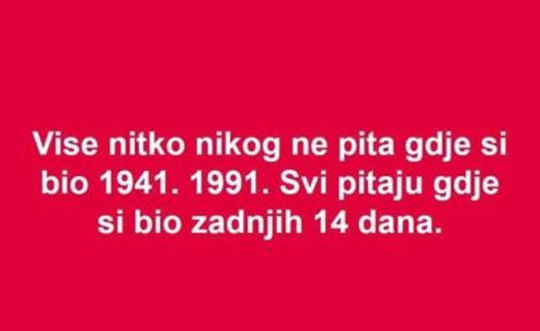

Example 2 Change in perception B

(No one is asking anyone where they had been in 1941 or 1991. Now everyone’s asking where have you been in the past 14 days)

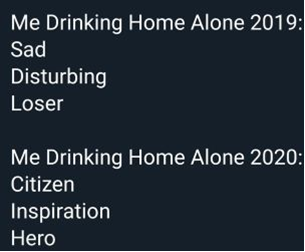

Example 3 Change in perception C

Types of humorous content

A vast majority of humorous content is graphically arranged almost to a professional level – in the case of video clips, one could notice above-average production quality. This property of the analysed humorous content tells us that the author of the content cares about the message being a) viewed/received, b) understandable, c) accepted and d) forwarded.

Regarding the classic division of content into text, image and video, in the observed corpus, most of the content was a combination of text and image.

Humorous content is mostly short – in most examples, it contains a single image or one graphically designed sentence. Video posts averaged 30 seconds in duration, with the longest funny video post in the observed sample being 1 minute and 33 seconds long.

The educational function of humor

Every message, including a humorous one, reflects some (one or more) intentions of the sender. Even if there is no intention, it is defined as intention.

Fortunately, humorous messages all have at least one purpose: to achieve the effect of humor in the recipient.

Humorous content can perform the function of raising awareness about a problem. According to Schmidt (1994), humorous content will be more often and more easily remembered, making humor a valid tool for the effectiveness of message transmission.

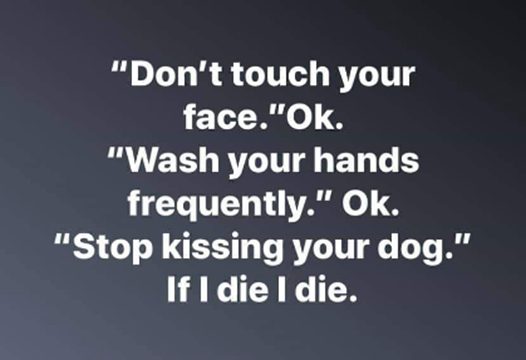

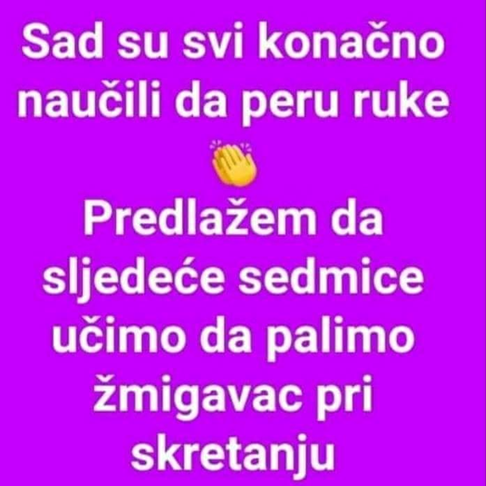

The educational function was performed by messages with the common denominator “It is important to adhere to preventive measures.”

Variations of expression when conveying educational messages take the following forms and connotations:

| – | Don’t be “stupid and incompetent” or “be less able to follow these simple instructions than a dog”; simple instructions: don’t touch your face, sit and wait, |

| – | even irresponsible “party people” behave responsibly and wear face masks and disinfect their hands at a group party; |

| – | “Stay home”, that is, do not leave your house. This message was found in several variations, from appeals to “stay home” to reprimanding people who do not “stay home” and implications that everyone who “stays home” is a hero (such as Superman); |

| – | Keep distance with the perhaps already familiar phrase “together yet separate” ; |

| – | Avoiding mass gatherings and criticising people who do not follow this guidance due to panic shopping; |

| – | Listing the symptoms of coronavirus; |

| – | The fact that dogs, and pets in general, are not contagious; |

| – | It is necessary to check body temperature; |

| – | Warning of current events that have been taken to the point of absurdity given the situation (“thanks to daylight saving time we will be able to stay home for an hour longer”); |

| – | Awareness of whether you are at risk due to old age; |

| – | How to make a face mask, which was a big problem due to the shortage of face masks; the chosen example shows how to make a mask from men’s boxers; |

| – | Education in some examples refers to the general knowledge that people should have, for example, alcohol as a frequently used sanitiser is flammable, so be careful when disinfecting and wait a bit before using a lighter; |

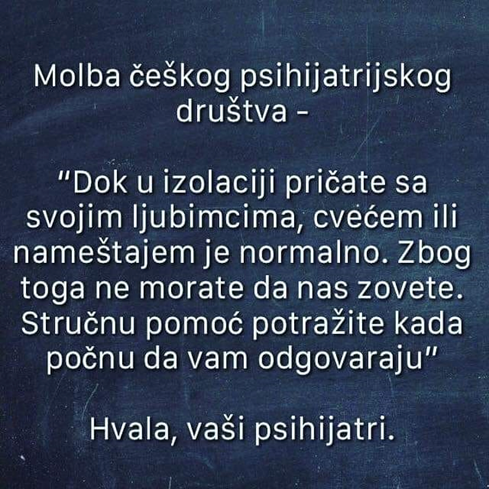

| – | Suggestions on how to bear to be constantly at home without going out, including a message from a psychiatrist about where the limit of insanity is (so education consists of judging for ourselves whether we should report in for psychiatric treatment or not) ; |

| – | Do not travel while you have a fever; |

| – | Raising awareness about the dangers of sitting at the computer all the time (because life has switched online), so a humorous message appears to remember to stretch your neck; |

| – | Do not shake hands; there are ways to greet people without physical contact; |

| – | The importance of listening to the official guidelines. |

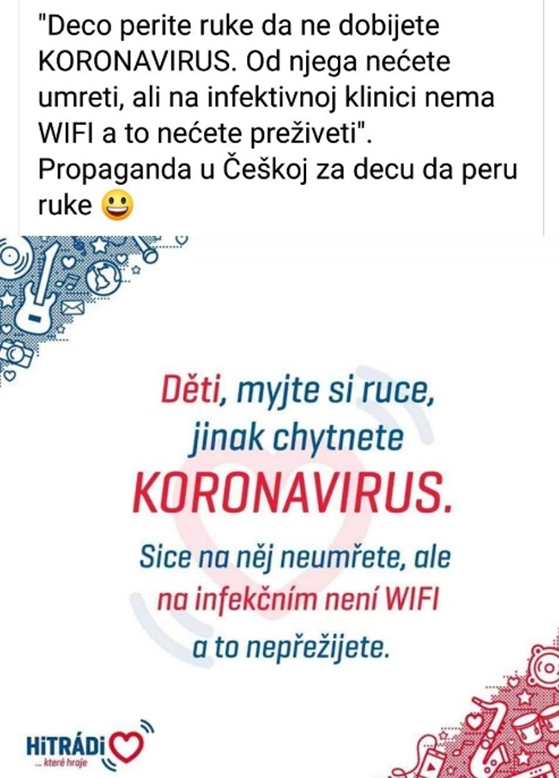

Example 4 Educational function A

(kids, wash your hands so you don’t get coronavirus. You will not die from it, but hospitals don’t have wifi and you would not survive that)

Example 5 Educational function B

Example 6 Educational function C

Example 7 Educational function D

(now that everybody has learned to wash hands, I propose that next week we all learn to switch on the turn signal when turning)

Example 8 Educational function E

(Checz psychiatric society plea – “Talking to to pets, flowers of furniture during isolation is normal. You do not need to contact us for that. You should seek for professional help when they start to talk back.” Thank you, your psychiatrist.)

Unforeseen problems arising from the pandemic

Caring, empathy and compassion for sick people is something that is not only natural to us, but is additionally encouraged in society and in education. If someone is in trouble – and disease certainly is trouble – help them if you can. Ultimately, this is one of the paradigms of all world religions – to help others.

The outbreak of the pandemic resulted in an increase in the level of empathy and care for loved ones (as indicated by the interview results). But on a personal level, that concern and desire to help was overwhelmed by fear of infection from known or unknown people (anyone nearby). This panicky fear of the possibility that I PERSONALLY would contract COVID-19 resulted in panic withdrawal from any symptom of the disease, such as sneezing, coughing, blowing one’s nose into a handkerchief, etc. All diseases – COVID-19 just being one of many – become perceived as something to move away from, something we don’t want to get close to and are afraid of.

Example 9 An unforeseen problem

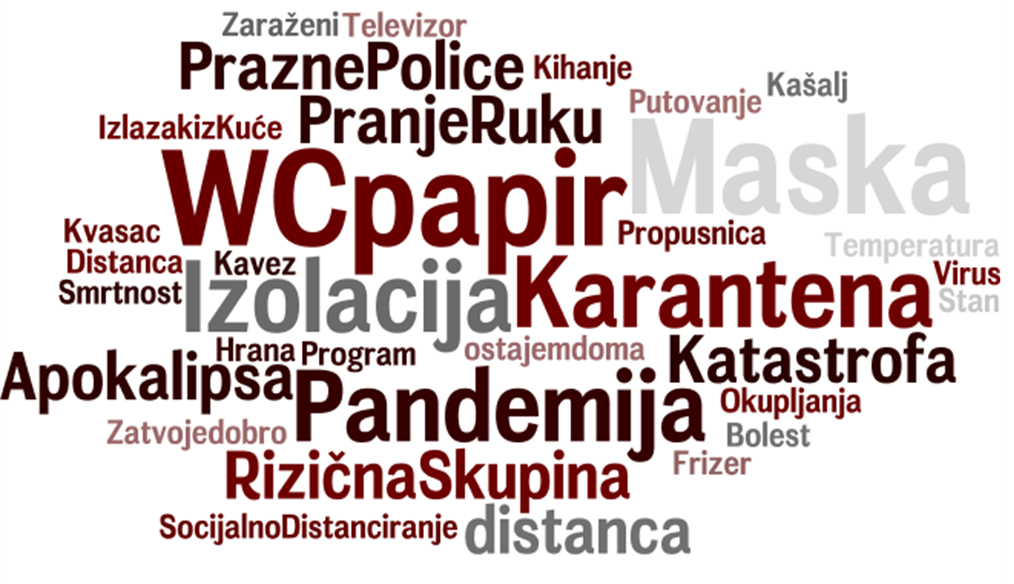

Coronavirus or COVID explicitly – keyword cloud

Based on the humorous announcements collected, it is quite obvious to all participants in the event that they deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequences it has on various aspects of life. For individuals who have not experienced this situation, this connection will not be obvious because the humorous content generally does not explicitly mentions keywords coronavirus or COVID. In fact, most of the collected posts do not contain a text, audio or image spelling out “coronavirus” or “COVID”. Hence, this chapter provides an overview of keywords or tags that researchers may use in the future when searching for content related to COVID-19, without the name being explicitly mentioned.

Display 1 Keyword/tag cloud

So, this is a visual representation of keywords or tags that are explicitly expressed by sound or text within the units of analysis (posts).

These words vividly show which vocabulary is often used to express humor.

To begin with, these are terms (expressed in text, sound or image) that are related to diseases: “virus”, “pandemic”, “cough”, “sneezing”, “temperature”, “risk group”, “disease”.

Terms such as “mortality”, “infection”, “apocalypse”, “catastrophe” also appear.

Furthermore, the terms used include various protective equipment that is necessary in a pandemic era such as face masks, but also other forms of protection, such as washing hands.

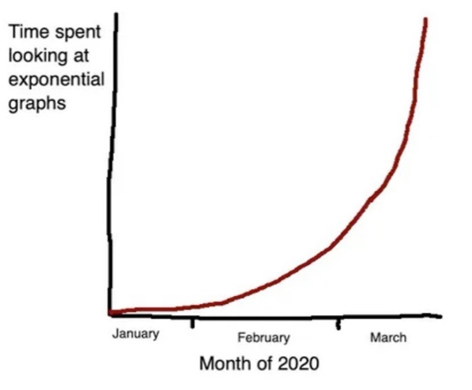

“Staying at home”, “leaving the house”, “isolation”, “quarantine”, “gatherings”, “a pass”, “distance” and “exponential graph” are terms that are strongly related to the vocabulary of responsible persons, but have also found their place in humor. We could also mention the term “cage”, which vividly represents how people experienced spending time indoors.

“Staying at home” takes on several language variants, such as the phrases “I’m staying at my house”, “I’m staying at home”.

As one of the results of staying at home, the terms “hairdresser” or “hairstyle”, “obesity” and “excessive eating” also appear.

A good portion of humorous posts talks about problems with supplies, where most posts ridicule the issue of a lack of toilet paper, yeast, or empty shelves. The word “supply” is often replaced by the word “shopping” or shop names.

Humor related to remote learning, which has become common for all school kids since mid-March this year, is mainly related to the terms “television” or (television) “programme”.

The phrase “for your own good” appears in a paternalistic and even patronising way, and it is presented mainly by animals (which are still pets to humans, and not the other way around). The same kind of humor, in which people and animals swap places, is found in all those funny posts in which animals are amazed by people wearing muzzles.

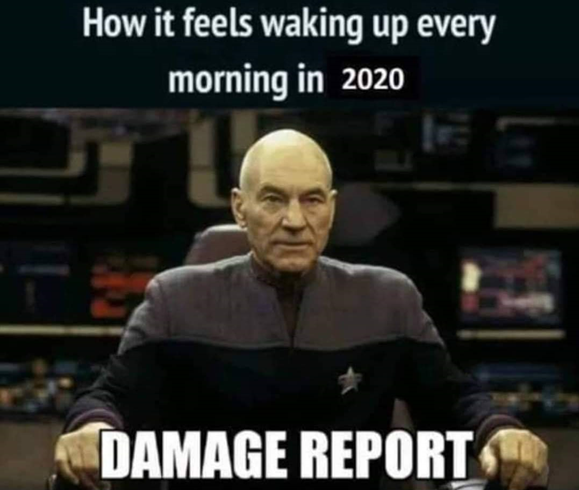

“2020” is often the only term that helps distinguish that humor is related to COVID-19 and its consequences on individuals.

However, there are also many posts that still cannot be explained by the simple keyword tags related to the situation, but are undoubtedly related to the COVID-19 humor.

Of course, making such a word cloud is not enough to cover every single post, because some humorous posts do not contain a single tag and yet relate to the coronavirus.

International or local?

The next research question refers to the territorial reach of humor. Can we argue that humorous posts are funny only locally or globally?

In an ideal world, we would look at the country of origin of individual posts and observe the spread through different areas and the applicability of humor in its original or modified form in different areas and further examine whether the representative population in each country considers each post humorous and in what way.

These large amounts of data were not available, so the corpus of collected posts was divided into two categories:

- Foreign or international post,

- Local post.

Within the observed corpus, a significant portion of humorous posts relates to local humor which takes already known elements (situations for example) and shapes them to fit the Covid-19 context.

The global or international character of messages is reflected in the following: the language of the message is foreign, mostly English. Internationally known symbols or people are used, or memes[170] as templates or GIFs that have already been used.

Local humorous messages are those that are in the Croatian language or use symbols, people, institutions, prejudices or phrases characteristic of Croatia. If this cannot already be called cultural heritage, then at least we can say that the specifics of the local cultural circle have found their place in the COVID-19 related humor.

The existence of international humor indicates connection and communication, perhaps even agreement, if not in the desire for improvement, then at least in humor with other countries. Perhaps it cannot be said that the similarities of humorous messages for different countries of the world show the same way of experiencing the situation, because the matter of perception of the received message cannot be approached only through similarity of content, but the existence of humorous messages accepted as humorous in different countries indicates similarity.

It was certainly interesting to note that some publications appear in foreign and Croatian languages, in different variations yet with the same message.

Example 10: The same message in two expressions and languages A

(#stayathome because it is not everyday that you can save the world in payamas)

Example 11: Same message in two expressions and languages B

These forms of communication lead to the conclusion that some content is the same for all areas affected by the same problem and that humor is equally applicable even without translation.

Target: Who is humor aimed at? And how?

Within the observed sample, the majority of posts are not related to any persons, groups or institutions. Still, some of the posts base their humor on famous persons or institutions.

There is a difference between the presence of (famous) persons or groups in the content of the post as a means of transmitting the message and those posts in which some characteristics of persons or groups are ridiculed.

The former category refers to the appearance of celebrities, institutions, or groups that serve as a means of conveying a humorous message. This use of an entity in humor is not aimed at ridiculing the entity – the entity is used because of some of its characteristics that supports the humor of the message, regardless of whether a given feature is used in its original meaning. Famous “persons” or entities can be divided into the following groups:

- Musicians (singers and bands)

- Actors (mostly related to a specific role)

- Politicians and institutions (foreign and national)

- Characters from fictional works (cartoons, superheroes, books)

Example 12 Presence of entities in content A

Example 13 Presence of entities in content B

The second categorisation involves observing who (or what) is being ridiculed as part of COVID-19-related humor. Because, not all posts that ridiculed someone included celebrities, nor are all posts that include celebrities also ridicule them (unlike the already observed category of occurrence of entities in humor).

So who is COVID-19-related humor making fun of?

The humor targets:

official persons (postmen, teachers), politicians (Boris Johnson, Putin, Trump, Manolić), institutions, organisations and events (Zagreb City Authority, Ministry of the Interior, Olympic Games), religion (Our Lady of Medjugorje, Jehovah’s Witnesses), groups (people from Herzegovina, Dalmatia, Islands of Brac, Germans, anti-vaxxers, vegans and vegetarians).

Almost all humorous messages that ridicule an entity base their humor on making fun of some of the previously known attitudes, one might even say prejudice.

Example 14 Presence of ridicule A

(coronavirus tried to enter the city council, but it was missing two papers and 20 kuna of revenue stamps)

Yet, there is a special category that surpasses the usual frameworks in which ridiculed entities are the subject of humor. A common feature of these posts is ignorance, primarily in terms of the use of face masks and the application of rules of conduct and hygiene. Although public figures who (intentionally or accidentally) do not follow the rules of hygiene and conduct are ridiculed, this is not based on an entity – the subject of ridicule may also be an unknown person who does not follow the rules of conduct.

Exaggeration is also a subject of ridicule, mainly when buying excessive quantities and stockpiling (mostly toilet paper).

Another form of ridicule (not related to well-known persons) is related to rules of conduct. Rules of conduct are ridiculed to the point of absurdity, or people who do not adhere to these rules are made fun of.

Example 15 Presence of ridicule A

What are we laughing at?

During the analysis, we tried to draw a thematic categorisation of posts, guided by the main question: “What is the topic of this humor?”

Consequently, we were able to extract the following content categories:

- Animals and pets – where the roles of animals and humans are swapped (man is trapped in his home/cage) or people are equated with animals, so now man wears face masks (while animals normally wear muzzles or collars). Animal-related humor is often closely linked to ecological ideas of how “nature strikes back”.

Example 16 Animals A

Example 17 Animals B

(they call me disobidient, yet half of them can not do “sit” and “wait”)

Example 18 Animals C

- Homeschooling or remote school, where the funny side of homeschooling is shown or posts are making fun with possible scenarios arising from that situation.

Example 19 Remote school

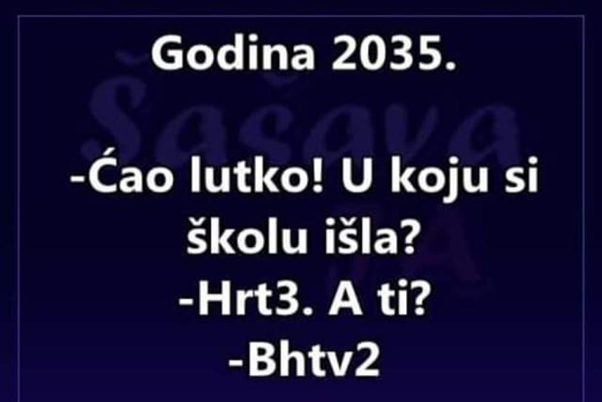

(year 2035. –Hey doll! What school did you go to? –HRT3. You? – BHTV2)

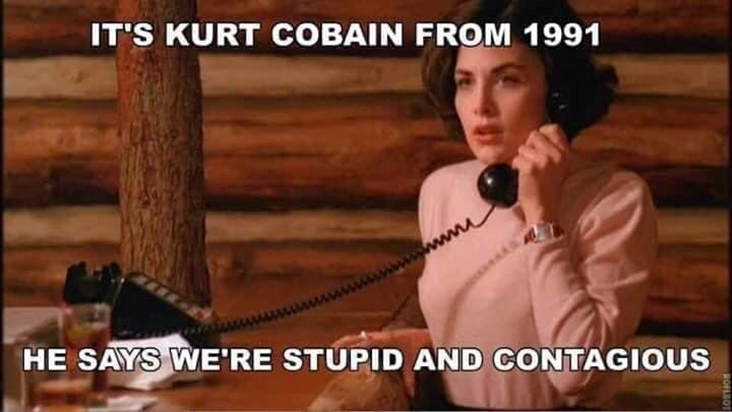

- Songs and films, where the words of previously published works are now given a new connotation.

Example 20 Songs and movies

- Politics, where politically significant individuals and parties are placed in a COVID-19 context.

Example 21 Politics

(they discovered that virus transferes form animals to humans)

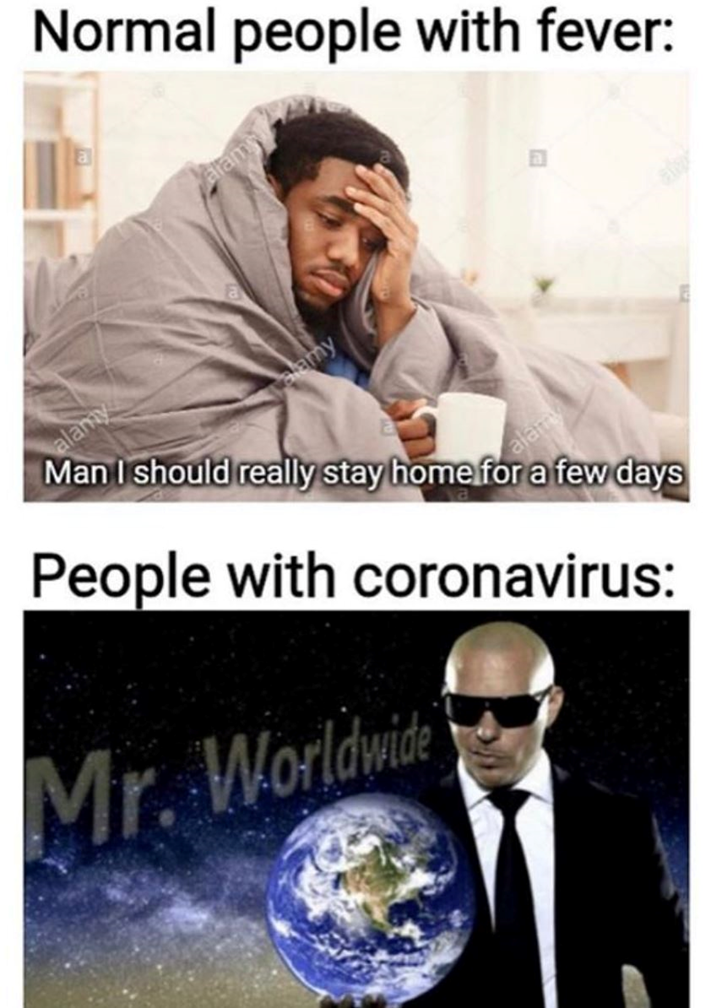

- Travel, where it is shown in various ways how COVID-19 positive people travel and thus infect others, or how some long for travel while “staying at home”.

Example 22 Travel

- Measures and rules of conduct that include hand washing, wearing face masks and social distancing, where the humorous side of the newly created situation when adhering to the measures, as well as the consequences of adhering to the measures, is presented.

Example 23 Measures

- Staying at home (isolation). The category of staying at home mostly contains posts that show what people are doing now that it is recommended not to leave their homes.

Example 24 Stay at home

(I am wondering where we might go for the weekend)

- Stocks and supplies, with posts speaking of stockpiling and consequently the issue of availability of certain items in stores.

Example 25 Supplies

(Battle at Konzum (shop name) (2020 Anno domini))

Dark humor

Humor varies from gentle, mild, positive or “cheerful” humor to extremely dark, negative and derogatory humor. The emergence of black humor as part of “disaster humor” (humor circulating immediately after a catastrophic event) is not new, but, according to Bischetti, Canal and Bambini (2021), “even though Covid-19 humor is inspired by

Example 26 Gentle/benign humor

Example 27 Dark humor

Emotions

The subject of the study from the aspect of emotions was based on two questions: how intensely the emotions were presented in the humorous content and which emotions were contained in the messages.

Emotions that could be read from the content of the messages are fear, despondency and despair, boredom, love and sympathy, mainly through the expression of humanity and anger.

The intensity of the displayed emotions varied depending on the content of the individual message, where most of the content did not have any strongly expressed emotion, and some did not include emotions at all.

Example 28 Emotions were not detected

Example 29 Strong emotions detected

(Emil and sedatives)

The issue of the reception of emotion was further explored through interviews.

Humor requires pre-knowledge

In order to understand humor, prior knowledge from some general or specific areas is required. In addition to knowledge about the situation or the necessary behavior and the “new normal”, to understand humor it was also necessary to have knowledge from movies, music, literature, politics, drug culture, sexual aids, prejudices circulating in society, video games, and decisions of the Civil Protection Headquarters (or measures).

Example 30 Content of humor that requires prior knowledge to understand

b) Interview

Humor as a coping mechanism for stress

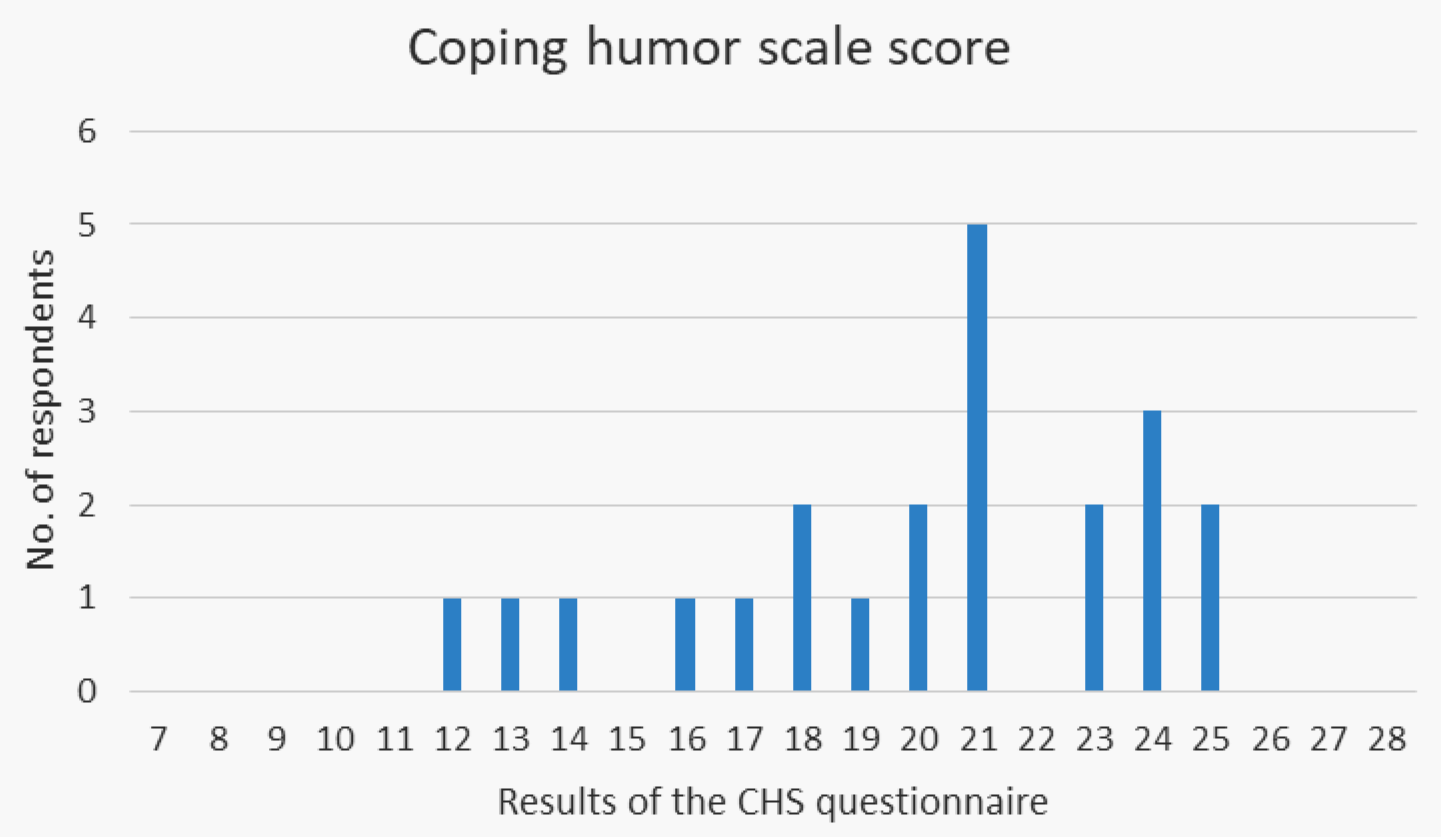

The average score of the respondents on the Coping Humor Scale (CHS scale) is 20. Values on the scale can range from 7 to 28, with the lowest score among respondents being 12 and the highest being 25. The results of 6 respondents deviate from the average standard value by more than one standard deviation, 4 respondents have a result significantly below the average, and two respondents significantly above the average.

Graph 1 Display of respondents’ results on the CHS questionnaire

But did all respondents really describe their experience in March 2020 as a stressful situation?

All respondents stated that they experienced negative emotions during March 2020. Only two respondents stated that their level of negative feelings in 3/2020 was the same as before while the remaining 20 stated that their levels of negative emotions were moderately or significantly higher than before. People who do not attribute negative emotions to COVID-19 and the consequences of the virus attribute it to the disease they were experiencing at the time or to the illness of their loved ones (not caused by this virus).

For the sake of control, respondents were also asked about the existence of positive emotions in a given period. Most respondents stated that negative emotions outweighted positive emotions. This is the range of positive emotions and events expressed in March 2020:

| – | Excitement because something new and different is happening, |

| – | More time for family, |

| – | Getting closer/connecting with family, |

| – | Freedom to set your own schedule (due to work from home), |

| – | Team spirit of colleagues at work, |

| – | Gratitude (because nothing terrible happened to me or my loved ones), |

| – | Initially positive because you have less contact with people who annoy you, but also reduce contact with people who do not annoy you, so it is good in the short term. |

17 out of 22 respondents noticed a significant increase in humorous content, while all respondents stated that at least half of all of the humorous content was related to COVID-19 and situations arising from the COVID-19 crisis.

Of all 22 respondents, only one described the effect of humorous content in March 2020 as negative. She said: “I would feel guilty if I laughed and something happened to someone,” and the emotions that the humorous content triggered at that time were described as “It made me angry: how can you joke about something like that?” It should be emphasised that this respondent has a low result on the CHS questionnaire, and that this person already in the third month of 2020 knew people who became ill and people who died from COVID-19. This respondent describes her personal experience of the situation at the time as a notably greater feeling of fear, confusion, financial and health uncertainty and insecurity. This respondent admits that in the following months (summer months) she could accept humorous content on the topic of COVID-19 and laugh at it, but at the beginning of the pandemic “it wasn’t helping. It wasn’t funny to me, and I didn’t take it as a joke, but really: what we will experience this year.”

Most respondents, on the other hand, believe that humor had a positive effect on them or their emotional state.

The values of the CHS questionnaire results correlated with the effect that humor had on the emotional state of the respondents. The effect of humor is divided into three groups: positive, negative and neutral. The correlation was calculated using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient, and stands at 0.506.

Table of printout of correlation results using Spearman’s correlation coefficient of ranks, in the SPSS tool

|

||||

Correlations |

CHS |

humor_score |

||

Spearman’s rho |

CHS |

Correlation Coefficient |

1,000 |

,506* |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

. |

,016 |

||

N |

22 |

22 |

||

humor_score |

Correlation Coefficient |

,506* |

1,000 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

,016 |

. |

||

N |

22 |

22 |

||

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). |

||||

Table 1 Spearman correlation

This medium-strong correlation proves that the character trait of the propensity to use humor in stressful situations is related to the studied experience in the specific stressful situation of the onset of the pandemic and lockdown.

How do respondents describe the effect of humorous content?

Respondents attribute the positive effect of humorous content to the following mechanisms, as stated in their own words:

| – | Relaxation, calming, |

| – | Joy, |

| – | Improving mood, |

| – | Laughter, |

| – | Shift from reality (“provides objectivity and a grain of common sense”), |

| – | Putting things back in balance, self-regulation, |

| – | Defence mechanism (“it’s easier to laugh at something than to be afraid”), |

| – | Connecting with others, togetherness, |

| – | Breaking down negative emotions, |

| – | Changing perspectives to a situation that was neither rosy nor optimistic. People did not lose their spirit, the sense of humor remained. |

In general, the positive effects of humor could be grouped as follows:

- Respondents experience laughter as a consequence of the humorous content received, but find that the effect of that laughter is very short-lived (a minute, two) and there is no long-term shift on a personal level because of that laughter.

- Respondents receive and send humorous content and thus connect with others in a group or community, or strengthen social ties, and describe a positive shift as a consequence of connecting with others where humor was a means of connecting.

- Humor helps on a personal level in a way that makes it easier for an individual to deal with a difficult situation.

The negative effects of humor were also investigated and their existence was noted with the respondents. One person, mentioned above, considered humor unacceptable and thus her overall experience of humor in 3/2020 was negative.

Other negative effects of humor are described as:

“Populist nonsense gets on my nerves, it annoys me. It’s not a healthy kind of humor, it’s caustic, and it’s humor that mocks/belittles/spits on others and doesn’t bring any joy.”

“It’s funny at first, but if you stop and think why you’re laughing then you start to feel bad about it.”

One of the respondents put a negative effect of humor into a group of humor related to conspiracy theories. He also provided the description of negativity: it is “humor that spreads panic.”

“Anger because I didn’t find it funny.”

“Despair was expressed through humor.”

“At first you laugh, but it also reminds you of reality.”

“One example annoyed me, but because I didn’t like the author, not because of the humor or message.”

Out of a total of 9[171] respondents who recognised the presence of a personal negative influence of humorous messages, only three persons attributed the negative effects of humorous posts as general rather than related to any particular group of humor (populism, conspiracy theories, personal preferences). This general negative effect is described as despair read between the lines of humorous posts or a reminder of the gravity of the situation. All of these three respondents described their condition as a higher level of negative emotions, describing humorous messages as a positive effect or a neutral effect, and it could be argued that the presence of negative effects of humor did not diminish the presence of a positive effect. In other words, the negative effects did not outweigh the positive effects of humor.

Noticing an educational note of humor

The researchers used the phrase “educational note of humor” to describe those humorous posts that contain messages about how to behave or not to behave. As some examples of educational content, we cite messages about washing hands, wearing face masks, distancing. During the interview, no distinction was made between the explicitly and implicitly stated educational messages in the content. Primarily, the researchers wanted to find out if the respondents noticed such content in humor. If respondents noticed it, they were asked if they felt that such humorous messages made them question and reconsider their attitudes and behaviors, and whether they might have changed their attitudes and behaviors.

Half of the respondents (11) said that they did not notice any elements in the humorous messages that would encourage them to rethink or change their behavior.

Respondents who noticed an educational note of humorous content agree that only a small portion of the content can be considered educational. One respondent said that based on a humorous message, he concluded that “You’re exaggerating, don’t buy so much toilet paper,” another said in a similar tone, “most of us still use these supplies – pickles, water, cans...” a third one said she considered how “maybe I should also buy toilet paper or flour.” Some respondents said that this educational function could only serve someone “who has no idea what is going on” so that now they wonder why they should wear a face mask or keep their distance.

In general, although there was undoubtedly an educational note in some of the humorous content, the messages were not primarily educational in nature and respondents did not notice many of them. To an even lesser extent, such messages made them reconsider their attitudes and actions or change their behavior.

Best according to respondents

Respondents were asked to choose the best humorous messages from March 2020. For the sake of simplicity, the researchers prepared about 50 humorous posts from the content analysis corpus before the interview so that respondents could recall the events and humorous messages of the time. Most of the respondents chose the best humorous messages from the corpus sent to them by the researchers.

The question of the best messages was left intentionally undefined because in the subsequent question the respondents were asked to explain in their own words why they chose these humorous posts. Most respondents perceived this question as the question about which posts they found the funniest. Some respondents, however, chose the best messages according to the following criteria: content related to the respondents’ profession (good graphic design or interesting visual expression); the content that was most often shared or that was the subject of further discussions; content that best affected the respondents’ everyday life. The following are the contents that most respondents mentioned as the best.

Example 31 The best post as chosen by respondents

Example 32 Second best post A

(I’ve imagined apocalypse with zombies, armed to the teeth, not staying at home washing my hands)

Example 33 Second best post B

(as electricians would say: better isolation than grounding)

Example 34 Second best post C

CONCLUSION

As part of the content analysis of humorous messages, it was detected that there was a change in perception in such a way that new circumstances made what was otherwise unacceptable or inappropriate acceptable and commendable. The existence of educational messages within humorous posts was recorded. Keywords have been recorded which may be used in future research to search for content when looking for humor from the COVID-19 pandemic period. The presence of local and international humor was detected. A categorisation of humorous messages based on the topic of the messages was made. Variations in the tone of humor (from gentle to dark) were detected and the prior knowledge needed to understand the messages was detected.

In the second part of the conducted research, the interview method was used to find out how the respondents experienced the received humorous messages in March 2020. The majority of respondents (14 out of 22) describe the effect that humorous messages had on them as positive, and only one respondent experienced a negative effect of the pandemic-related humor. The results of the Coping Humor Scale questionnaire show a large correlation with the effect that humor has on respondents (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.5), which confirms that the positive effect of humor is related to how much respondents tend to use humor in dealing with stressful situations. Also, the majority of the respondents detected increased negative emotions compared to the “normal” period before the onset of the pandemic, and most of the respondents found that humor helped them at least in the short term. The mechanisms to which respondents attribute the help that humor provided to them in dealing with a stressful situation are: connecting with others and change of perception – humor gives you a break from the situation and helps take the edge of a stressful situation.

Most respondents were both senders and recipients of humorous posts, thus connecting with others they know to share their opinions on a particular topic, while maintaining virtual contact. Also, some of the respondents stated that they were impressed by the ingenuity and speed of production of humorous messages.

In March 2020 in Croatia, humor was a form of a response to the new situation. People used humor to establish and maintain contacts with others. Also, using the content of humor and prior knowledge needed to understand the message, we can draw conclusions on general topics that were of interest to most citizens at that time: COVID-19 pandemic as such, problems with household supplies, how to respect social distancing measures and use a face mask and sanitisers, how we are reduced to (dis)obedient animals, the problems of closed service facilities, and the feeling of general boredom that many felt at the time.

Through this indicative research, we gained insight into people’s reactions to a dramatic event through humor. Further research should be population representative and place more emphasis on the experiences of individuals compared to the group they share humorous content with.

[162] This paper primarily refers to the period of March 2020. In the meantime, the vaccine has been tested and released, while the medicine is not yet available

[163] https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/ - accessed 10.09.2020

[164] https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/worldwide-graphs/#daily-cases – accessed 10.09.2020

[165] https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/worldwide-graphs/#daily-cases- accessed 10.09.2020

[166] https://civilna-zastita.gov.hr/vijesti/8 - accessed 10.09.2020

[167] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_responses_to_the_COVID-19_pandemic - accessed 10.09.2020

[168] https://civilna-zastita.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/CIVILNA%20ZA%C5%A0TITA/PDF_ZA%20WEB/Odluka%20-%20mjere%20ograni%C4%8Davanja%20dru%C5%A1tvenih%20okupljanja,%20rada%20trgovina.pdf – accessed 10.09.2020

[169] humor. Croatian Encyclopedia, online edition. Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 2020. Accessed 24. 11. 2020 <http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=26678>.

[170] “Meme” is am image, video, part of text etc. Mostly humorous in nature that is copied and quickly shared via the Internet, often with minor modifications (author’s description)

[171] Not counting one respondent who experienced a completely negative effect of humor

References:

Berk R.A., (2010.), The Active Ingredients in Humor: Psychophysiological Benefits and Risks for Older Adults, Educational Gerontology, 27:3-4, 323-339, https://doi.org/10.1080/036012701750195021

Bizi S, Keinan G., Beit-Hallahmi B., (1988.), Humor and coping with stress: A test under real-life conditions, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 9 (6), 951-956,https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(88)90128-6

Biscetti L., Canal P., Bambini V., (2021.), Funny but aversive: a large- scale survey on emotional response to Covid-19 humor in the Italian population during the lockdown, Lingua, Volume 249 https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/efk93

Chimuanya, L.-, & Ajiboye, E. (2016). Socio-Semiotics of Humor in Ebola Awareness Discourse on Facebook. In R. Taiwo, A. Odebunmi, & A. Adetunji (Eds.), Analyzing Language and Humor in Online Communication (pp. 252–273). Information Science Reference. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0338-5.ch014

Dundes A. (1987.), At Ease, Disease—AIDS Jokes as Sick Humor. American Behavioral Scientist, 30(3):72-81 https://doi.org/10.1177/000276487030003006

Gubanov N.N., Gubanov N.I., Rokotyanskaya L., (2018.), Factors of Black Humor Popularity, International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Ecological Studies (CESSES 2018), Atlantis Press, 379-383, https://doi.org/10.2991/cesses-18.2018.85

Henman, Linlinda D. (2001.), Humor as a coping mechanism: Lessons from POWs. Humor-international Journal of Humor Research - HUMOR. 14. 83-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.14.1.83

Lefcourt H.M., (2001.), Humor: The psychology of living Bouyntly, Kluwer Academi/Plenum Publishers, New York

Kalapoš, S. (2002.), The Culture of Laughter, the Culture of Tears: September 11th Events Echoed on the Internet. Narodna umjetnost, 39 (1), 97-113. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/33236

Kuipers G. (2002.), Media culture and Internet disaster jokes bin Laden and the attack on the World Trade Center, European Jurnal of Cultural studies, SAGE Publications, London, Vol (5) 450-470 https://doi.org/10.1177/1364942002005004296

Kertcher, C., & Turin, O. (2020). ‘Siege Mentality’ Reaction to the Pandemic: Israeli Memes During Covid-19. Postdigital Science and Education, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00175-8

Morrow, P.D. (1987.), ‘Those Sick Challenger Jokes’, Journal of Popular Culture 20(4): 175-84 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1987.00175

O’Toole G. (2013), Sustainable Web Ecosystem Design, Springer, New York

Oring, E. (1987.), Jokes and the Discourse on Disaster. The Journal of American Folklore, 100(397), 276-286. doi:10.2307/540324

Raskin V., Ruch W.,(2008.),The Primer of Humor Research, Mouton De Gruyter, Berlin, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110198492

Semmel, S., (2020.), ““Things are Going to Get a Lot Worse Before They Get Worse”: Humor in the Face of Disaster, Politics, and Pain, Honors College. 625. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/625

Schmidt, S. R. (1994.), Effects of humor on sentence memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20(4), 953–967. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.20.4.953

Šošić I., (2004.) Primijenjena statistika, Školska knjiga d.o.o., Zagreb

Tkalec, S.,(2008.), Humor: Teorije humora i Paulsov model, Hrvatsko komunikološko društvo i Nonacom, Zagreb

Torres, J. M., Collantes, L. M., Astrero, E. T., Millan, A. R., & Gabriel, C. M. (2020), Pandemic Humor: Inventory of the Humor Scripts Produced during the COVID-19 Outbreak. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3679473

Yovetich NA, Dale JA, Hudak MA. (1990.) Benefits of Humor in Reduction of Threat-Induced Anxiety. Psychological Reports.;66(1):51-58 https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.66.1.51

Internet sources:

Civil Protection; https://civilna-zastita.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/CIVILNA%20ZA%C5%A0TITA/PDF_ZA%20WEB/Odluka%20-%20mjere%20ograni%C4%8Davanja%20dru%C5%A1tvenih%20okupljanja,%20rada%20trgovina.pdf – accessed 10.09.2020

Civil Protection; https://civilna-zastita.gov.hr/vijesti/8 - accessed 10.09.2020

Wikipedia; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_responses_to_the_COVID-19_pandemic accessed 10.09.2020

World health organization; https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/ – accessed 10.09.2020

Worldometer; https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/worldwide-graphs/#daily-cases – accessed 10.09.2020

Humor u doba COVID-19 pandemije

Sažetak

Istraživanje je usmjereno na sam početak pandemije COVID-19 u Hrvatskoj – ožujak 2020. Predmet istraživanja su humoristične poruke povezane s pandemijom. Kombinacijom kvantitativne i kvalitativne metode, ovo istraživanje je pokazalo kako su ispitanici intervjua doživjeli primljeni humoristični sadržaj vezan uz korona virus te kakve su sadržajne karakteristike humorističnih poruka detektirane kroz analizu sadržaja.

Ključne riječi: Covid-19, korona, recepcija humora, sadržajne karakteristike humorističnih poruka.